Psychic Lepers,

Hunchback Burglers

and the Way to God

A

Critical edition of works by the Hindi Bhakti poet Bājīd

List of

works included into the edition

The

poet Bājīd

Recent scholarship has pointed out the extraordinary contribution of the small north Indian sect, the Dādūpanth, to the emergence of Old Hindi manuscript culture and to the preservation of the earlier oral lore of Nāmdev, Kabīr, Raidās and many other poets (e.g. Horstmann 2003, Rajpurohit 2013). Several prominent Dādūpanthī authors systemathised the sect’s teaching, while others, such as Bājīd (Vājid or Bājind, fl. 1600), the subject of this project, were more independent in their poetic output with a wide range of poetic subjects. Bājīd was once one of the most popular Dādūpanthī authors, his works were widely copied in handwritten books and his independent quatrains in the arill metre are still current in the oral lore of Rajasthan, and storytellers often quote them to prove their words (Maheshwari 1980: 126 and Simhal 2007: 51). His arills have been previously published in books with circulation restricted mostly to the Dādūpanth (Visharad 1932; Mangaldas 1948; Rajnish 2004; Simhal 2007). Nevertheless, one of these volumes inspired the modern guru Osho to deliver discourses on Bājīd (Osho 1995). This published material, however, forms only a small part of Bājīd’s literary output. In manuscript catalogues more than a hundred different works of his are mentioned. Thus, Bājīd is one of the most dramatic examples of how literary tastes changed with the advent of print culture as he has largely been forgotten in colonial and nationalist literary histories. In Dādūpanthī sources Bājīd is counted among the direct disciples of Dādū Dayāl while in the wider literate and oral world in Rajasthan he has been popular for his arills, a poetic form of which he was considered to be the best exponent.

Images

of Dadupanthi saints at the Sundardas

Memorial in Sanganer, Rajasthan

Bājīd’s arills express general nirgun Sant teachings. Similarly to the dohās, arills are good vehicles of short religious or general moral messages but their length allows more scope for poetic imagery or verbal play than that of the dohā.

How long can you remain negligent, my friend,

when King Death counts the breaths of this life?

Awake! Be attached to God’s name! How long will you sleep?

And indeed, whatever falls into the millstone will become flour.

(2 Sumiran kau aṅga, 4)

Bājīd, however, was a prolific author with more than a hundred works. Most are predominantly dohā-caupāī compositions of fifteen to about a hundred couplets each. There are also two anthologies of dohās, which prefigure the massive Dādūpanthī Gańjanāmās and Sarvāṅgīs. Along with producing arills and dohā-caupāī works, Bājīd also composed in the emerging new meters of kuṇḍaliyā, jhūlnā and nisānī and his Rekhtā is the earliest known long composition in the dialect of modern Hindi.

The majority of his longer poems are designated nāmo in their titles, a Brajified version of the Persian word nāma ‘book’. By this he was imitating Mughal Persian literature to an audience that did not necessarily knew Persian but surely respected its status. Although the majority of Bājīd’s works are in unpersianised Bhasha, he systematically retains the Persianate words dīvān, as a designation of a representative of God, who acts as a worldly lord, and dargāh for his court. Moreover, unlike Dādū, Bājīd wrote relatively few pads, the most widespread means of communal singing. Bājīd’s works abound in references to writing. For example, fate is expressed in his Kaṭhiyārā-nāmau with the words likhe/likhyau or kalām, both meaning ‘what has been written’.

Most of Bājīd’s compositions deal with issues important to the Nirgun Sant tradition without being sectarian or explicitly expressing allegiance to Dādū Dayāl or the Dādūpanth. His preferred themes include the pain and longing of the devotee for union with the ineffable being and the contrast between false or true devotion. He attacked human shortcomings in the ‘Book of the dull’, ‘Book of the disgraced one’, ‘Book of the negligent’, or the ‘Book of the quarrelsome woman’. Some of the titles, such as the ‘Book of the Sufi’, ‘Book of the king’, ‘Book of union’, the ‘Book of love’, echo the wider Persianate culture of North India at the time, albeit in a more popular form. Among the most oft-copied manuscripts of Bājīd’s dohā-caupāī works are several entertaining narratives presenting features of oral performance, such as ‘The omens of the blind and the decrepit’, or ‘The story of the previous birth of a king, a carpenter, a merchant and a leper’.

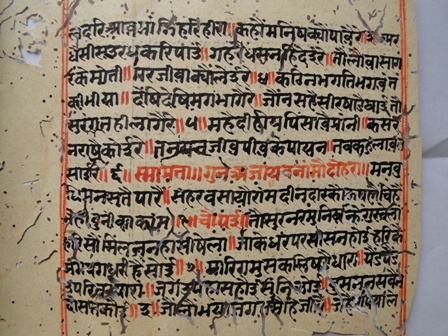

The beginning of

Bājīd’s Ajāyab-nāmo,

"Book of wonders", in an undated, warm-eaten manuscript.

The

Project

The critical edition of Bājīd’s works prepared by Dr Imre Bangha (University of Oxford, UK) and Prof Daksha Mistry (MS University, Vadodara, India) will make available a representative selection of the literary output of this author to a wider academic readership. It will present thirty minor works of Bājīd collated from eighty manuscripts. Uniquely in early modern Hindi literary culture, there exists a relatively large amount of manuscript material produced in the poet's lifetime or shortly after his death. This early material and its precise chronological dating provide a firm basis for the study of subsequent transmission.

During the past twelve years the editors have undertaken research tours to locate and copy manuscripts of Bājīd’s works in various collections in Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. By 2013, all accessible manuscripts of each of the 30 works have already been consulted and many of them has been photographed. The text of each work will be a reconstructed, metrically correct scholarly text with its non-ortographic variants in the critical apparatus. The apparatus will be accompanied with notes on both the main text and the variant readings making the text accessible for people not be fully acquainted both with Brajbhasha and Dhundhari, the literary idioms of the works. Through the accompanying introduction and annotated translation of some selected works and passages it will be of interest also to students of early modern literary cultures, of Hinduism and of religious and literary syncretism who may not have acquaintance with the language.

Publications

Bangha,

Imre: ‘Unearthing a Forgotten Poet: Vājīd

in Legends and in Manuscripts.’ Acta Orientalia Scientiarum

Hungariae (2011), vol. 64, no. 1, 2011,

pp. 1-12. DOI 10.1556/AOrient.63.2010.3.2.

‘A curious King, a Psychic Leper, and the

Workings of Karma: Bājīd’s Entertaining Narratives.’ In Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield (ed.): Tellings

and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance Cultures in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2015, pp. 359-381 (ISBN 978-1-78374-104-5, http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0062).

List

of works included into the edition

Vol. I.

Edited by Imre Bangha and Daksha Mistry, Introduction and translation by Imre Bangha

Texts from the Oldest Manuscript (1600AD)

|

1 |

Čaupāī — Četāvnī ke aṅg kī |

|

2 |

Hari-upades |

|

3 |

Nām-mālā |

|

4 |

Arill |

|

5 |

Čīṭhī |

|

6 |

Prem-nāmo |

|

7 |

Sākhī

satī nāmā kī |

|

8 |

Čaupāī (Čit upades) |

Narratives

|

9/28 |

Rāj-kirat |

|

10/6 |

Kaṭhiyārā-nāmo |

|

11/2 |

Sagun |

|

12/4 |

Ātma upadeś |

|

13/19 |

Parpańc-nāmo |

|

14/3 |

Bilaiyā-nāmo |

Against Shortfalls

|

15/7 |

Karkas-nāmo |

|

16/10 |

Gauṁgāī-nāmo |

|

17/18 |

Nīč-nāmo |

Teaching

|

18/1 |

Ajāib-nāmo |

|

|

19/5 |

Utpatti-nāmo |

|

|

20/9 |

Gambhīryog Grantha |

|

|

21/11 |

Ghaḍiyā-nāmo |

|

|

22/16 |

Nirańjan-nāmo |

|

|

23/17 |

Nirmal jog |

|

|

24/25 |

Brahma-čaritra |

|

|

25/26 |

Śrīmukh-nāmo |

|

|

26/31 |

Sonaciṛī saṁvād |

|

Divine Love

|

27/20 |

Prem-kahānī |

|

28/27 |

Muhabbat nāmo |

Free-standing poems

|

29/8 |

Kuṇḍaliyā |

|

30/14 |

(Guṇ)

Jhūlno |

Vol. II. (Edited by Imre Bangha)

Polemics

|

23 |

Patisāh-nāmo |

|

22 |

Bājīd-nāmau |

|

3 |

Anabhai-nāmau |

|

30 |

Sūfi-nāmo |

|

?33 |

Māyā-kirat |

Free-standing poems

|

29 |

Rekhta |

|

|

Nisānī |

Vol. III. (Edited by Imre Bangha and Daksha Mistry)

Anthologies

|

|

Virah-vilās |

|

|

Gun Ganjnāmā |

Sample

work

To see the edited pdf version of Nām-mālā, "Garland of divine

names", click here.

(Vowel signs may not appear fully

in some browsers.)

Contact

us

With any observation please

contact Imre Bangha.